This archive – which is now in the possession of Lorrendraaier – contains communications between the Dutch Departement van Defensie (DvD) and N.V. Koninklijke Hollandsche Lloyd (KHL) shipping company. Dated a few years prior to World War II, they detail secret communication codes and measures KHL’s merchant ships should take in case of another war.

by Caitlin Greyling

During the post-WWI and pre-WWII interwar period, tension was rife, especially in the 1930s during Hitler’s rise to power. Many nations had secret codes in place to ensure safe communication in case war broke out again. However, these codes needed to be communicated in the utmost secrecy to ensure enemy forces weren’t able to decipher them.

This archive features many such secret code-related correspondences from the late pre-WWII period. The first is dated 15 November 1934, and they continue until 21 April 1936. The correspondences were handed out in sealed envelopes, many of which were marked “Secret.”

Confirming The Identity of the Crew

At the time of communications, the KHL shipping company had 13 named merchant ships in its fleet. All of which the DvD wanted to check were manned by Dutch captains, helmsman, and wireless operators before distributing communications. This, despite many of the men entrusted with handling them having non-Dutch surnames like Martinelli, Dodero, Lowies, and Hirschfeld.

These were times of pre-war, though, so it’s possible that the aforementioned names were aliases. Most of the envelopes were handed out in foreign ports, including Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires, which would further substantiate the logic of using a region-specific alias surname for the sake of secrecy.

Naturally, some members of the KHL ship crew were of other nationalities, such as Spanish or Portuguese doctors and Polish translators, as was often stipulated by the harbours of destination.

However, all of KHL’s ship captains, helmsman, and wireless operators were Dutch. After the KHL confirmed such with the DvD, each vessel was sent a sealed envelope via diplomatic services containing the codes and instructions. Each was marked with a unique number corresponding to the vessel number. The envelope was supplied with a cover letter, as well.

Receipt and Handling of the Codes

The captain of each vessel had to sign a receipt for the envelope. The archive also sheds light on the fact that pre-existing codes were in place, as part of the receipt process was to return any old codes to the DvD for safekeeping. You see, if enemies were to get ahold of old codes, they might be able to use them to decipher new codes or the entire coded language.

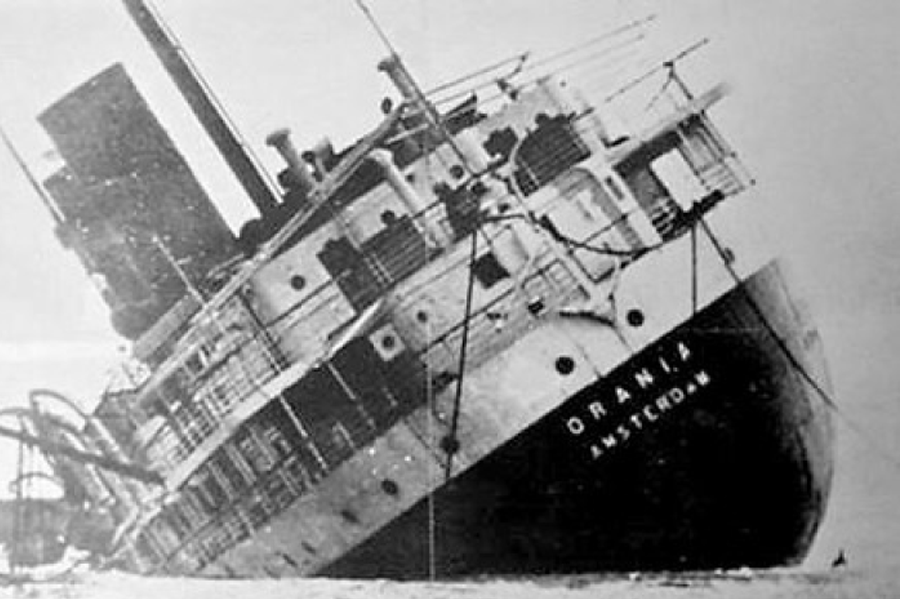

In a letter to the DvD, the KHL informs them that an old code for the vessel Orania could not be returned, as she sank in the Portuguese harbour of Leixoes after colliding with the Portuguese SS Loanda.

In a letter to the DvD, the KHL informs them that an old code for the vessel Orania could not be returned, as she sank in the Portuguese harbour of Leixoes after colliding with the Portuguese SS Loanda.

The aim of these codes, which could be transmitted through communication equipment onboard the vessel, was to:

- To communicate the neutrality of the merchant ship when asked to identify itself should a war break out.

- To be used for instruction purposes when leaving or entering a harbour.

- In order to interpret incoming messages (who the senders of such messages are isn’t clear in the communication).

- To request for radio silence.

Vessels Named

The archived correspondences name the KHL vessels that were supplied codes, but only 8 of the 13 alluded to are named. They are the:

It is possible that the names of some of the ships were not explicitly mentioned due to the nature of the correspondences. However, it’s more likely that there were multiple ships with the same name, as maritime archives record 5 KHL ships named the same but with differing construction years: the Amstelland (1900 and 1920), Eemland (1905 and 1906), Gaasterland (1903 and 1913), Salland (1905 and 1920), and Zaanland (1900 and 1920).

The Included Instructions

The captains were also supplied with instructions along the codes that detailed how to act in the event of another war. These instructions were not mandatory, and the correspondences in the archive also show that they differed and were amended frequently.

In short:

In case a war breaks out between befriended nations, or if the Netherlands is involved in such a conflict, KHL merchant ships are to:

- Sail to the nearest safe harbour.

- The captain should seek contact with the consul general of the Netherlands.

During the Great War (WWI), two or more merchant ships formed a convoy. The experience during WWI is that unescorted convoys seemed more often to be subject to attacks. Merchant vessels were, therefore, advised to sail alone, not in a convoy, unless escorted by a navy warship.

Then, three different scenarios are described as to what to do in the case of:

I – NL take a neutral position when a war breaks out:

- Radio silence at all times.

- All communication equipment should be manned 24/7.

- Try to only sail the territorial waters of neutral countries.

II – NL is part of the conflict:

- All of the above.

- Try to reach a neutral harbour as soon as possible.

- Do not use the normal sailing routes.

- Avoid busy routes and zones. Try to pass through such zones by night.

- Leave harbours shortly after darkness has set in.

III – NL is at war:

- All of the above

- Except, only sail at night and make sure all lights are blinded.

Naturally, this must have been incredibly dangerous. It’s no wonder many vessels collided with each other. Sure, when it’s a full moon, you still have reasonable sight. But what about when it is pitch black?

Documents contained in the archive:

- Correspondences between the “N.V. Koninklijke Hollandsche Lloyd” and the Dutch “Departement van Defensie” (Ministry of Defence).

- Receipts signed by captains that they received the envelopes.

- Cover letters from KHL to the captains, accompanied by the envelopes with codes.

- A list of who handed over the cover letter, code, instructions, when, and at which port.

- Instructions [9 pages].