Ship-in-a-bottle models have been washing up on the antique market for centuries. Each unique in shape and form, we can certainly argue that our new addition is still an exceptionally peculiar one — if the lazy way out!

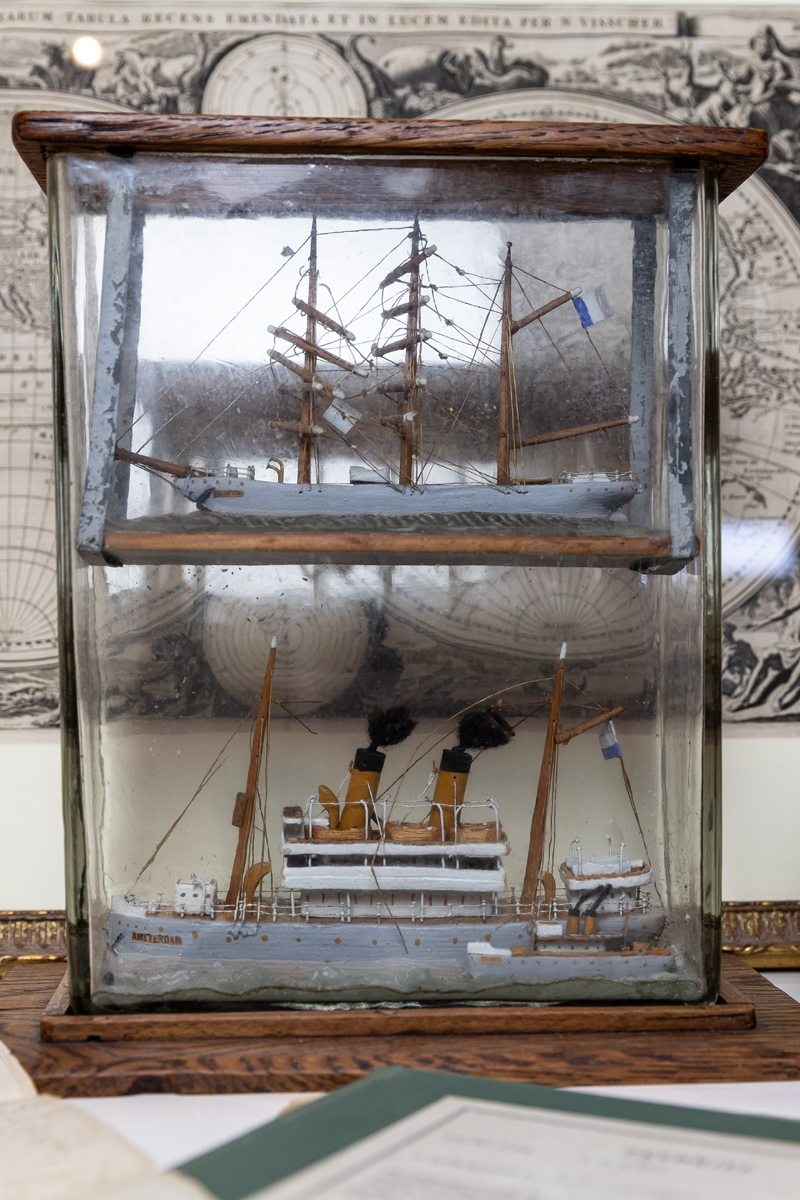

In a square, open-top glass container sits three vessels — a three-mast sailboat and, below it, a steamship accompanied by a tugboat. It’s clear to see that our ship in a bottle wasn’t as difficult to create as the typical ones we know of. The linear top of this clear glass container provides plenty of clearance to slot the ships in after being built.

A cheat as far as building ship-in-a-bottle models goes! After all, the idea (and achievement and wonderment of them) is to build the ships inside by dropping elements through their typically narrow necks. Regardless, our miniature has an interesting story to tell, though its origins and date of creation were a challenge to trace!

Steamships such as our Amsterdam were introduced to The Netherlands around the mid-19th century. That’s 100 years after the Dutch East India Trading Co.’s Amsterdam sailboat was built. Or around 50 years after the VOC was dissolved in 1799.

Steamships such as our Amsterdam were introduced to The Netherlands around the mid-19th century. That’s 100 years after the Dutch East India Trading Co.’s Amsterdam sailboat was built. Or around 50 years after the VOC was dissolved in 1799.

Waving A Friendly Flag

Luckily, we have some guidance as to where to start in the form of the flags each ship flies. At first glance, the flag that the sailboat, the Batavia, is flying appears to be that of France, as its stripes are vertical. However, this flag may just be positioned oddly, as the steamship Amsterdam’s flag features horizontal stripes characteristic of those on the flag of The Netherlands instead.

Since all of the boats (including our tug) feature names associated with The Netherlands, this is quite possible. However, The Netherlands was under the control of France and Napoleon at the turn of the 18th century under the name of the Batavian Republic.

Alternatively, the flag of the Amsterdam (or both boats) could be that of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) or Dutch East India Company (in English) instead. It flew the same flag as The Netherlands — but with the “VOC” emblem on it. Founded in 1602 of various independent Dutch companies operating since 1594, it’s not to be confused with its British-ruled rival, the East India Trading Company (founded in 1600). Additionally, the name of the ships themselves also hints at this fact.

A Homage to Two Dutch East India Co. Ships?

The Amsterdam (1748) and the Batavia (1628) were both sailboats that were part of the Dutch East India Company’s (VOC) fleet. And the town of Hoorn was one of the six chambers of the VOC. Therefore, it’s a fitting name for a tugboat servicing it, its harbour, and these two boats.

Both the Batavia and the Amsterdam were also Spiegelretourschip (mirror return ship) — one of the most important types of ships in the Dutch East India Co.s fleet. Ships such as these embarked to Batavia from The Netherlands to drop off passengers and supplies to the VOC colonies located in Asia and the Indies. They then made their way back to Europe laden with spices, china, and more exotic wares.

Unfortunately, both ships were shipwrecked — the Amsterdam in 1749 and the Batavia in 1629. Coincidentally (and very ill-fatedly), each just a year after they were built and set out on their maiden voyages. The coincidences don’t stop here. Both ships were also finished on the 8th year of a decade and shipwrecked on the 9th of one, too. Perhaps our model sought to remind its creator of this ill-fated coincidence (and more).

Based on the estimation that 100 guilders = € 5500 (in modern-day currency), that’s around €5.5 million. The demise of the Batavia and Amsterdam was certainly a sorry loss for the VOC, we can imagine. Not to mention the additional loss of cargo and casualties each’s demise may have levied on the VOC ledgers.

Likely used as a vase or display container prior, our pressed glass container also features a carved oak base and lid.

Likely used as a vase or display container prior, our pressed glass container also features a carved oak base and lid.

Two Ill-Fated Dutch East India Co. Vessels

The Amsterdam failed to complete its maiden voyage to Batavia in the East Indies (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia, near the central base of the VOC in Java) at all. It sank near Hastings in the English Channel, which is much closer to home than the shipwreck of the Batavia. It sank near Morning Reef on the Houtman Abrolhos islands off the coast of Australia, also failing to complete its maiden voyage to Batavia. Hence, potentially, why the Amsterdam is accompanied by a tugboat called “Hoorn,” which would be perfectly positioned to pull it to safety closer to home. Yet, the Batavia sails alone.

Amongst the Amsterdams maiden voyage cargo were chests of silver guilder coins, textiles, wine, ballast, cannons, domestic goods, and more, equating to several million euros in today’s money. Unluckily, after several unsuccessful attempts (and a mutiny), the Amsterdam was finally grounded in the mud of the bay of Bulverhythe on 26th January 1749 after its rudder broke off in a storm. Ill-fated indeed! Though, the most valuable supplies were reportedly salvaged (from the seas and pillagers).

The Batavia didn’t fare much better, also (nearly) experiencing a mutiny while at sea. Two notable passengers — the ship’s commander, Paelsart and his deputy, Cornelisz — were tempted by the ship’s valuable cargo, scheming a mutiny. When the ship was separated from the rest of its fleet (mirror return ships usually travelled in convoy) at the Cape of Good Hope, they thought it was their chance.

However, bad luck struck just before when it ran into the Morning Reef in the early morning hours of June 4th. What ensued after the Batavia shipwreck is one of the bloodiest survival stories on account, peppered with betrayal, scheming, looting, murder, and executions. However, its survivors were reportedly some of the first European settlers of Australia, however short their stay.

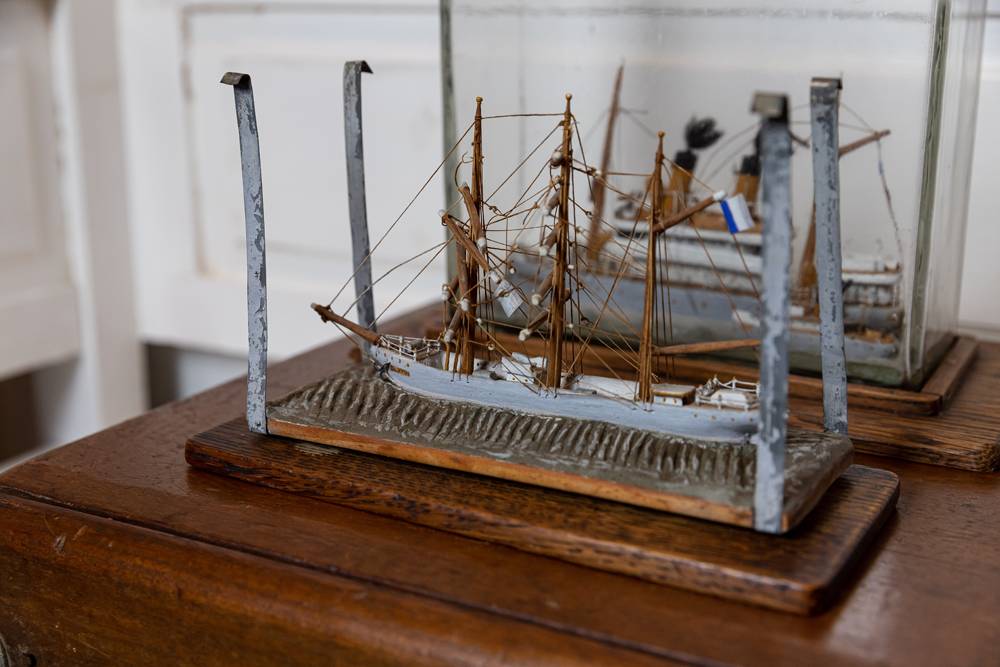

Are our Batavia and the VOC’s ill-fated Batavia mirror return ship one and the same? Conveniently, it comes out of its glass container, so that we can examine it more closely.

Are our Batavia and the VOC’s ill-fated Batavia mirror return ship one and the same? Conveniently, it comes out of its glass container, so that we can examine it more closely.

Alternate Theories

The only issue with my Dutch East India Co. (VOC) ship theory is that the Amsterdam is clearly a steamship, which VOCs Amsterdam certainly wasn’t. The other ship, the Batavia, could also be a model of a less notable ship of the same name. First named Anna Justina, then later renamed Schagen, it was first registered in 1856 in Amsterdam.

That said, it’s possible that this miniature model was created before the Amsterdam and Batavia’s shipwrecks were found (again, eerily close together) — the Batavia in 1963 (by lobster fisherman Dave Johnson) and the Amsterdam shortly thereafter in 1969 (after it was revealed by a low spring tide). So our craftsman didn’t know that the Amsterdam wasn’t a steamboat when he built it.

A factor that would also account for the differing features of our ship models versus their full-size replicas, which you can now view in person. Before their wrecks were found in the 1960s, their dimensions and finishes would only have been communicated in etchings, written word, or tales. Of course, it’s also possible that the discovery of both vessels’ shipwrecks was the inspiration for the creation of our ship(s)-in-a-bottle.

The general public would have been unlikely to know their true dimensions until their real-life replicas were finished decades later in the 1990s, as well. The pressed glass container also alludes to such a date. Glass of this sort was popular from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th (1850-1950). All taken into account, these factors likely date our model’s creation to around 1950-1970.

Steamships such as our Amsterdam were introduced to The Netherlands around the mid-19th century. That’s 100 years after the Dutch East India Trading Co.’s Amsterdam sailboat was built. Or around 50 years after the VOC was dissolved in 1799.

Steamships such as our Amsterdam were introduced to The Netherlands around the mid-19th century. That’s 100 years after the Dutch East India Trading Co.’s Amsterdam sailboat was built. Or around 50 years after the VOC was dissolved in 1799.

Comparing Ship Replicas to Model

The life-size replica of the Batavia is moored as a museum ship in Lelystad in the Netherlands and is based on accurate measurements from its shipwreck. Sadly, the wreck of the Amsterdam hasn’t been excavated, even though it is reportedly one of the best-preserved VOC ships ever found. However, a life-size replica of it does exist, viewable, moored next to the Netherlands National Maritime Museum.

Another coincidence? The build of both ships’ replicas started in 1985! Though the Amsterdam’s replica was finished early in 1990, while the Batavia’s replica took a further five years to build, finishing up in 1995. Regardless, neither’s replica seems to match our model, which is a shame. However, since our craftsman seems somewhat of a novice, we could just attribute this factor to clumsy fingers. And, perhaps, some fanciful imagination!

If you have any clues as to the identities of any real ships more closely associated with our ship model, do let us know! Or, you can assist us with unravelling the mysteries of another of our other collectables — such as these 20th-century ship watercolours or 19th-century steamship diorama.